Microservices 101 ft. DDD: The good, the bad & the ugly.

Introduction

A couple of months ago, I had the pleasure of being sent by work (we're hiring! 👀) to one of the largest Software Developer Conferences held in the United Kingdom - NDC London 2019. I spent five days there, attending Sam Newman's brilliant workshop titled Designing Microservices for the first two, followed by numerous thought provoking talks the following three days.

To stick to my guns regarding my recent lightning talk (which I shall blog about soon) on the importance of knowledge sharing within organisations, I've been putting together my own internal watered down version of the workshop that will allow me to relay most of the key information that I learnt, back to my colleagues. It is split in to five separate parts.

This post will summarise the points made in the first of the five of my workshop sessions where I covered the basics behind what exactly microservices are, problems with the monolithic architecture it looks to potentially replace, the pros of a microservice architecture, the cons of a microservice architecture until finally concluding with a little look at what Domain-Driven Design and Event Storming are and why they are key components towards achieving a well modelled microservices architecture.

I will also make my slides available at the bottom of this post, along with a potential video recording of it when it becomes available. However, if you are going to watch the video then I'd strongly recommend you refer back to the contents of this blog post where I will go in to more detail regarding points and things might make more sense! Otherwise, this article will probably hit the spot a bit more than the video will.

Bounded Contexts

In order to provide some context (pun fully intended) for the remainder of this post, it is crucial that you understand what a bounded context is in Domain-Driven Design.

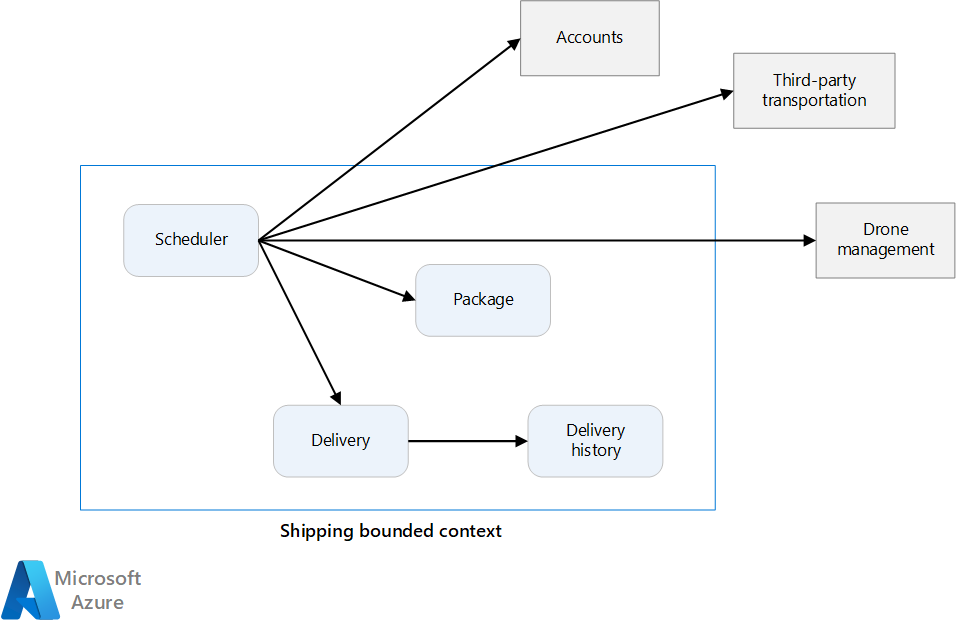

A bounded context is a logical boundary within a business domain, that defines a specific responsibility within that domain. Everything within said boundary is the implicit, non-ambiguous responsibility of that bounded context and only that particular bounded context.

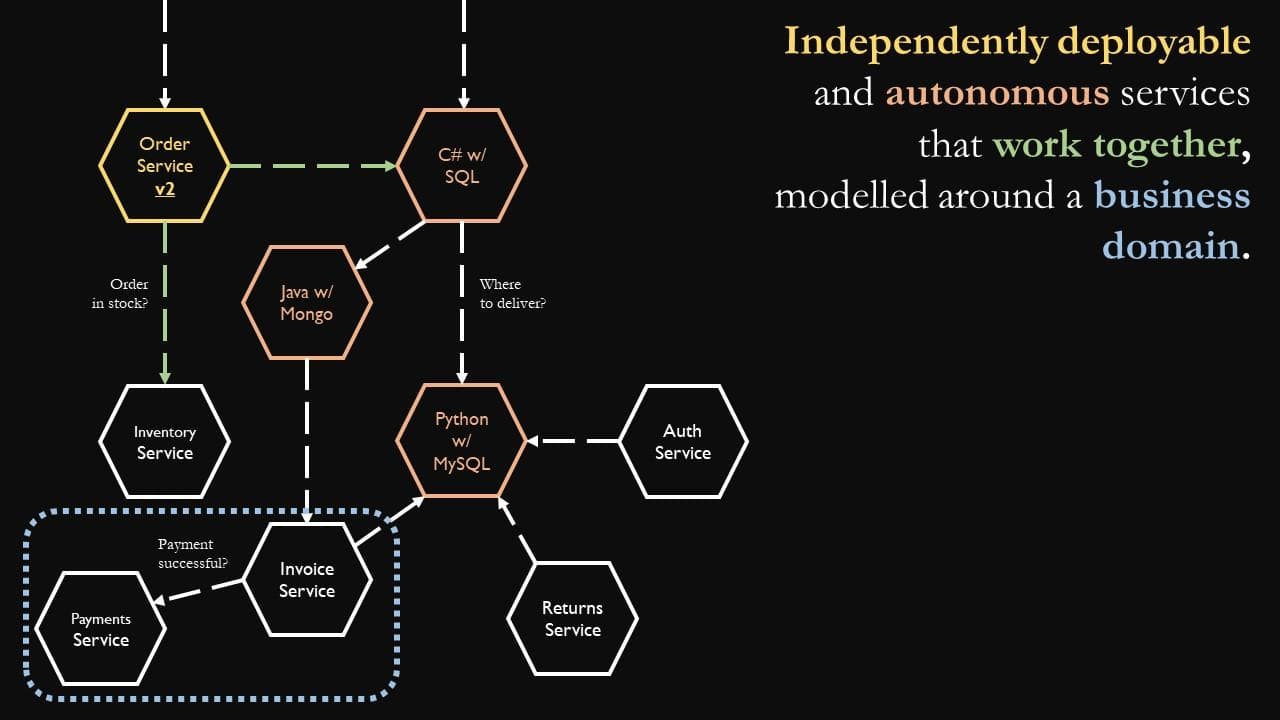

How does one define a microservices architecture?

Independently deployable and autonomous services that work together, modelled around a business domain.

Thanks again to Sam Newman for the awesome definition. Go drop him a follow on twitter whilst you're at it. He also has a second version of his book called Building Microservices being released in September 2019 on Amazon that you should check out or pre-order.

Independently Deployable

By being able to independently deploy smaller, isolated and individual services that focus on and deliver a single responsibility, we can therefore ensure that we resultantly have smaller and quicker deployments which is advantageous. We'll take a look at this in more granular detail later in this post. This attribute of a microservices architecture is a great example as to why businesses shouldn't even consider a microservices architecture if they do not have adequate CI/CD practices. The old saying about there being no point in building a house without a solid foundation comes to mind.

Work Together

More than often, our microservices will communicate asynchronously via either API calls or through a messaging/message-broker system such as RabbitMQ or SQS or perhaps even a data stream such as AWS's Kinesis.

Autonomous

Autonomy in context of a microservice from a technical view point can potentially mean several different things. This can range from the ability to easily utilise decoupled technology stacks - for example, one microservice can be running and written in Python utilising a MySQL persistence layer whilst another on the other hand, can be written in C# utilising a NoSQL MongoDB persistence layer - all the way to something as simple as, you guessed it, being independently deployable and not needing to be concerned with any other services or data stores except its own. This can also be applied from a non-technical perspective which ties in to how this approach can create domain experts, both from the development side as well as the business side.

Business Domain

For those familiar with the concepts of Domain-Driven Design, the simplified idea behind it is to provide an approach that allows business organisations and their structure to define how we as software developers design and model our systems so that they both resultantly model and correlate against each other as closely as possible.

It is worth noting in advance that this can of course still be achieved without the use of a microservice based architecture, however to truly benefit from microservices, the services themselves must be defined based on good domain modelling, otherwise problems may arise later.

Microservices tend to provide a single service which should equate to a bounded context within our business domain model. Note that bounded contexts may be large and made up of one or more aggregates. It isn't incorrect to opt towards instead of encapsulating all the aggregates within a bounded context in to a single microservice, opting to split your microservices up further based on each aggregate. But going forwards we'll just focus on bounded contexts in general as it still satisfies our definition of microservices being modelled around a business domain area. So if there's one point you should understand and carry with you as you continue reading this post, it is that in order to successfully utilise a microservice architecture it is crucial to understand that we must understand how to define what the bounded contexts within our business domain model are first, prior to starting any development of decomposition of our systems.

We will touch on a technique called Event Storming towards the end of the article which is a fantastic workshop that aims to provide a cheap way of domain modelling with plenty of sticky notes (we all love sticky notes, right?) and is also great at helping us identify these mysterious bounded contexts.

Conway's Law & co.

Microservices are an interesting topic of discussion among developers. We've probably all heard the poorly argued suggestions in the past that the approach is a mere "fad" or "buzzword" and is nothing more than just decomposing bigger systems needlessly into smaller, more complicated systems.

Believe it or not, I'm inclined to agree that the act of "just decomposing bigger systems needlessly into smaller, more complicated systems" is unnecessary and creates extra headaches and confusion for developers. The issue is, is that the art of decomposing monolithic applications into microservice architectures is more than that and so it is unfair to try and pin the blame on the architectural style itself.

When the developers don't actually understand what exactly within their monolith should be decomposed and as a result end up blindly creating a bunch of chaotic small services everywhere without the preposition of correct domain modelling, it will inevitably lead to problems.

After all, would you dare try build a building without providing the builders with the architect's well thought out blueprints beforehand? In this type of scenario, while you will still reap some of the benefits we will discuss later in this article, the negatives will eventually outweigh them and you may dread your decision. The same way you will end up with some sort of building, but it'd take a brave man to enter it.

Once correct domain modelling is achieved, only then can we answer the million dollar question. Namely, how do we decide where our bounded contexts within our domain model lie? Once we know where the different bounded contexts lie within our domain, only then can we make a well informed decision on who or what should and shouldn't be an independent and autonomous chunk of our system.

"Organisations which design systems (well)... produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organisations."

- Melvin Conway, 1967.

"If the parts and relationships of an organisation do not reflect the parts and relationships of the (software) product, then the project will be in trouble. Therefore make sure the organisation is compatible with the product architecture."

- Jim Coplien, 2004.

"When you design a system, if the features can be broken into loosely bound groups of closely bound features, then that division is a good thing to be made part of the design. This is good engineering."

- Sir Tim Berners-Lee, 1998 (Principles of design)

So to summarise these quotes in to developer layman terms, if greater than one bounded context of your business organisation aligns to a unified domain of your software, this will inevitably result in friction that results in organisational headaches, software headaches and less time spent drinking coffee. Correctly defining bounded contexts within our business domain helps us prevent this.

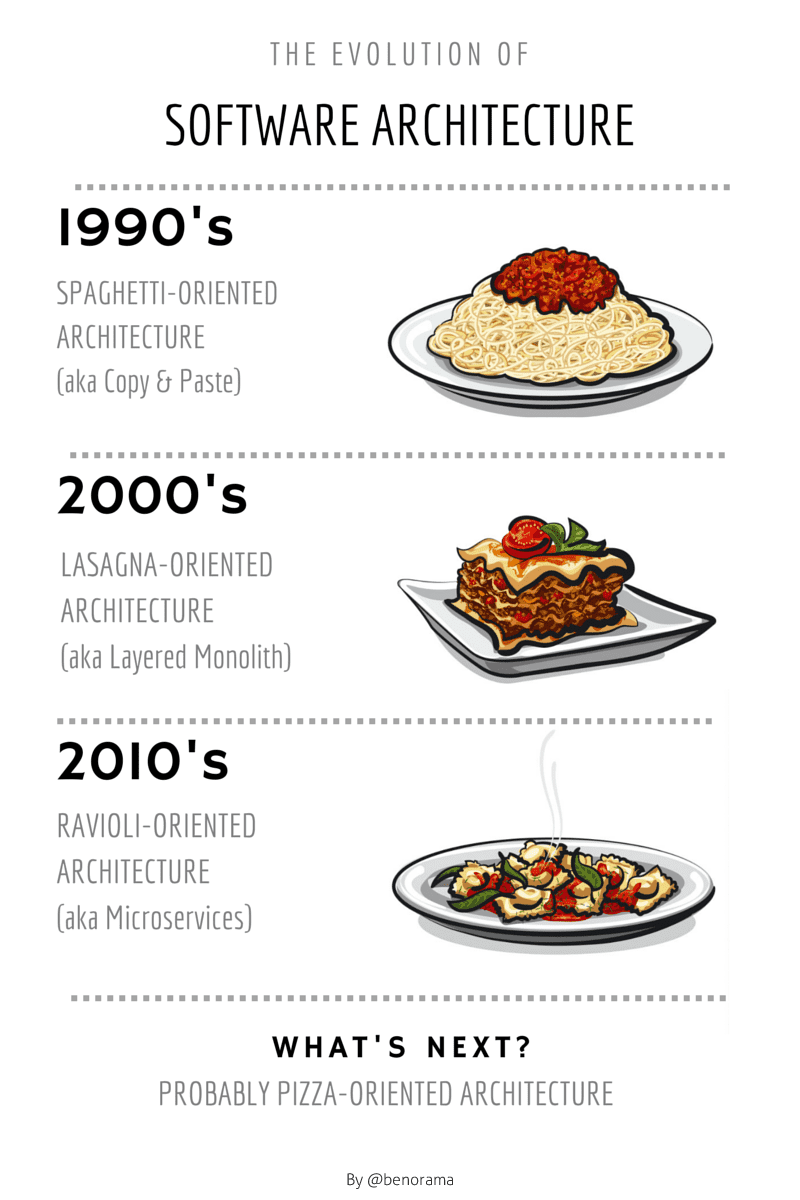

Image Source: https://medium.com/@benorama/the-evolution-of-software-architecture-bd6ea674c477

Food for thought

Paint the scenario where rather than having a department of software development domain aligned teams, all who each possess their own services or products that correlate only to the specific domain to which they cater for and are a delivery function for, alternatively to a department with numerous software development teams who instead are fed different types of projects from across a whole business instead where each project could spread across several different business domains where the codebases are essentially owned by and modified by everyone. The latter on a small scale, perhaps a small number of projects and developers is manageable. However on a larger scale, chaos will inevitably ensue.

The latter scenario being in place, makes it highly more likely that the businesses software is made up of coupled applications that over the years have been designed as all in one applications to solve a general problem or end to end project, rather than supplement several domains to provide a distributed solution across different teams (e.g. the same movements we would be seeing occurring in the business).

For example, the small scale business has a customer service that was developed once upon a time, because businesses tend to need some sort of software that deals with customer related concerns, right? Over time, as more business requirements become evident and projects trickle through to different development teams, anything remotely related to customers just gets conveniently added in to this ever growing customer service and new tables, you guessed it, added to the same database. Now this isn't the end of the world, but over time it will become increasingly more difficult to sustain and grow this customer service. Once businesses and systems grow and become increasingly more complex, this is when problems start to creep in and some disadvantages of monolithic architecture may start to appear. Or quite simply, as the business evolves, the software doesn't because of the added overhead that comes with needing to do so.

Resultantly, it eventually becomes inevitable then that different teams would be required to dip in and do their development in to the same single or several monolith(s) that hold(s) more than one business domain concern. If we consider only the development headaches that could potentially stem from this such as something as simply obvious as the inability to truly own a software system's whole deployment life cycle (Hey Bob, is it okay if I deploy your team's unfinished, merged changes? Are they feature switched off?) and the resultant lack of autonomy due to sharing your codebase with other development teams who may or may not cater for a completely different business function than you, is it not worth at least being open minded to the idea that there may be a better, viable alternative?

If we take an ecommerce business such as Amazon as an example, who actively practice microservice architecture as an example and dumb things down in terms of how their business probably functions on a simplified high level, are the non-IT members of the business who belong within some sort of product fulfillment/delivery/sales business domain working in the same department, let alone within the same team as the people who are responsible for pricing products? The answer is no and whilst this split may seem logically obvious and a natural choice upon which we should also be reflecting in our software to avoid coupling through developing software for the business, upon reflection of these business domains in detail rather than this simplified high level view, it may become clear that our software boundaries may not actually align with how our business aligns. For example, just because fulfillment and delivery both have something to do with a warehouse, doesn't mean the same business function are responsible for both domains. In fact, they are both very different and provide very different capabilities to the business.

After a bounded context is identified, it may be made up of numerous aggregates that too can be considered as candidates to become microservices. Image Source: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/architecture/microservices/model/microservice-boundaries

Domain-Driven Design will go even further as to state that our software should be written using ubiquitous language - defined by Eric Evans as common language between developers and users, structured around the domain model - so that even your non-technical stakeholders can probably understand their corresponding business processes written in code - to a certain extent. This hints at our variables or events within our code being named using the same language, the business uses. If a bunch of developers leave, the non-technical business members should be able to explain exactly what does what to the new developers and vice versa.

Software or code is meaningless without context. As a software developer who works with pricing systems in my day to day job, the most difficult part of my job has always been trying to extract from stakeholders, not just how certain processes or calculations take place but also the ifs, buts and whys. If you don't truly thoroughly understand a problem that you are solving, are you actually able to engineer the best solution possible let alone any king of solution through the software you write or are you only translating user stories/tickets on a board in to code that sort of works?

Blood, sweat and tears is shed trying to extract knowledge from business stakeholders and trying to find some sort of common ground. Event Storming will help us understand domains and extract business processes from our stakeholders in such a way that we are then able to model our software on it. It is a highly effective workshop technique that comes pretty close to being able to finally deliver that. As of early last year, ThoughtWorks decided to adopt Event Storming on their technology radar. The awesome thing about Event Storming is that it can be as high level or granular as the facilitators want. This means you can use it to learn about a whole business, a single domain or even apply it to merely a single use case.

Image Source: https://www.boldare.com/blog/event-storming-guide/

So, back to where we first started. Nobody should be walking in to work tomorrow and changing their world in to lots of smaller services for the sake of it, nor should a microservice architecture ever be considered the "default architectural choice" for a software application as the trade-offs and pre-requisites (one of the most common being software functions lacking maturity in terms of their continuous delivery practices) may not always be right for you and your software function.

However despite this, a microservice architecture remains an extremely powerful asset within a developer's toolbox when you not only believe that the functional benefits in context of both your domain as well as software function, are something you would benefit from and would outweigh the negatives. But most importantly it could all become a massive headache if you don't actually model your business domain that will eventually resemble the structure of your software correctly.

For example, whilst the ability to split and assign team boundaries to result in software development teams split on domains requires a strong high level understanding of the business, there must also be a detailed understanding of the bounded contexts within these domains upon which microservices could and most likely will be split. As a result, if both sets of bounded context's for the business domain model are flawed, this can eventually still result in coupling between microservices which will inevitably lead to problems, complications & affect how well we can reap the benefits of microservices in the first place. Do bear in mind that figuring out these boundaries is a very difficult task and that it isn't unusual for companies/software development teams to not get everything right the first time round when adjusting.

It's also worth noting that whilst every Microservice should be based on an identified bounded context, not every bounded context necessarily requires to be a microservice. An identified bounded context may be made up of lots of smaller bounded contexts, sometimes identified as aggregates during the event storming process. In this case, the parent bounded context could be how we actually go about splitting development teams and the child bounded contexts could define the microservices that are then owned by that domain.

Monoliths

A single-tiered software application containing numerous unaligned components that have different concerns and as a result the project lacks modularity.

A nice explanation and contrast that illustrates the difference between a monolithic application and a microservices architecture is the one below courtesy of Martin Fowler.

Image Source: https://www.martinfowler.com/articles/microservices.html

Monoliths: The Problems

Highly coupled and shared codebases

- More than often, with other development teams.

- This can lead to teams stepping on each others toes or merge hell.

- As a result, development can become tedious, more difficult & progressively slower.

Poor scaling

- Large monolithic applications are bigger and may also contain a greater number of tests and therefore project builds may be resultantly slower.

- Monoliths can be less cost effective as it is more flexible to have lots of smaller (potentially serverless) servers that can be scaled up or down easier. You can also gain greater control over spend such as in a scenario where you can auto scale based on load versus one large, more expensive server that is not very flexible. Thus, it is possible to flexibly dedicate more resource where required.

High risk big bang deployments

- Businesses know time is money and that the slower development & deployments take, the less money the business is making. Lower risk, smaller and quicker deployments speed up time to ship code out to the market.

RIP new developers

- Whilst it can be argued that monoliths are easier to debug (thanks F12), larger code bases that handle numerous business concerns can also turn in to huge plates of spaghetti-oriented architecture (see image below) making them difficult to comprehend.

Monolithic testing

- So, you've made a one line code change?

- Brb, go grab a coffee whilst the build & 100 unit tests & 500 end to end tests that don't even touch or are impacted with the change you've made run.

Potential technological limitations

- Most of the time, your single application will be limited to one language/technology stack. Two if you're lucky and are building a single page application!

- The same applies to potentially being limited to data persistence technology or bus messaging technology or other technological choices. For example, if Bob has installed NHibernate with Castle Windsor in to the monolithic application, I'm sure Alice is going to have a fun time also installing and setting up the MongoDB driver simultaneously. What if Alice prefers AutoFac? Now these are obviously unrealistic scenarios but it highlights the lack of flexibility at lower level than even technology stack.

Microservices

We've spoken a lot at this point about assessing the trade-offs of microservices when determining whether or not one wants to even consider it as an architectural approach to solve a problem at hand.

Microservices: The Good

Decoupled and segregated codebases

- The monolithic issue around requiring coordination across teams no longer exists as one team and only one team are concerned with one segregated codebase within their domain.

- Some teams may opt to assign ownership of different sub-domains (in this case, modelled by one or a set of microservices) to individual members or pairs of teams to create domain experts.

More stable contracts

- Due to potentially tighter coupling in monolithic applications, it opens greater potential for knock on effects that lead to contract changes - particularly if something as simple as a models are being shared. Meanwhile in a microservice architecture, due to the smaller and decoupled codebases, changes deployed will much more likely potentially only affect the blast radius of the deployed microservice versus the potential within a large monolithic application with plenty of reliances across the business.

Improved independent scalability

- Generally, it is easier to scale & develop smaller codebases. So in this case, scalability can refer to infrastructure scale or functionality scale within a system.

- Infrastructurally, it is easier (and potentially cheaper because we can dedicate more resource only to the areas that require it) to scale a smaller, independent application.

- Functionally, it is easier to add new functionality in to smaller codebases.

Happier new recruits

- Smaller codebases are easier to understand and comprehend by people who lack an in depth end to end domain/business knowledge.

- Developers always want the opportunity and autonomy to experiment and try out new technology. This approach easily allows them to do so.

Smaller & faster deployments

- Less big bang = lower deployment risk.

- Less risk = inclined to deploy more.

Smaller test suites

- Less code that needs to be tested per deployment.

Easier to adopt new technologies & substitute out the old

- Since microservices are autonomous, other systems that communicate with them don't have to care what technology stack they are implemented in.

- This is a stark contrast to large, monolithic applications where different concerns live in the same codebase and as a result more than often have to share technology stacks or persistence layer choices.

- It is very easy to re-implement an existing microservice in a different technology stack and substitute it in for the old. As long as the communication contracts remain consistent, users of the service need not be concerned by it.

In some cases, eased security concerns

- In an ecommerce business, a main security concern lives within customer facing systems such as a checkout/basket system that handles payment details. Whilst internal applications may not require development specific added security concerns to be taken in to account and thus potential development time can be saved and eased.

- It's much easier to build a wall and moat around a small castle, than a larger one.

Microservices: The Bad

Increased debugging complexity

- When dealing with a single application within an IDE, it is for example, quite easy to F12 in to method calls, debug and trace code.

- When dealing with microservices that communicate asynchronously, relying on REST calls or messaging systems, this becomes more difficult to create the traceability. For example, you will be required to pull and run each microservice in from source control as a simple example of one of the several factors that will have to align in order to allow you to debug your code adequately.

Monitoring complexities

- This ties in with the previous point made that as we now have greater points of contact throughout a business process, log aggregation or the use of logging tools such as Kibana or Logstash become a requirement otherwise quite literally, prepare to solve a murder mystery every time something goes wrong.

Added communication complexities

- When dealing with a single application, calls to methods that exist in sibling classes are easy and cheap to make without much added overhead.

- However in contrast, when relying on communication between services through the use of REST calls or messaging systems such as RabbitMQ, added potential complexities include latency and the need for extra resilience to be introduced such as a circuit breaker solution to cater for if RabbitMQ is down.

A lack of consistency between teams

- Whilst we spoke earlier about giving teams tech stack autonomy being an advantage, to some businesses this may have an adverse effect if their development practices and lines of communication are not up to scratch.

- What happens when the developers with knowledge in a particular tech stack (language or data persistence choice) leave the business?

- Is this a viable long term strategy for some businesses?

Eventual consistency

- Building on the potential latency issues we touched on earlier, a bi-product of this is obviously the time it will take to propagate data & ensure data is consistent throughout all systems.

Testing becomes more complex

- It is much easier to integrate end to end testing within single monolithic applications.

- The added overhead of dealing with several services through asynchronous calls, makes the process of writing end to end tests more complex.

In other cases, added security concerns

- One of the advantages of microservices that we discussed earlier, was eased security in certain cases however as with a lot of things in any sort of engineering principle, there is always a trade-off somewhere and it is these trade-offs that play a part in our decision making.

- Now that we are sending data cross-boundaries versus being passed internally within a single application, factors need to be taken in to account such as should data sent between microservices be encrypted? What attacks are we now susceptible to that we were not before?

Microservices: The Ugly

The distributed monolith anti-pattern

- Do you still have to deploy different systems together? If you want to deploy service A, are you able to do so independently of also having to deploy service B?

- Is your service truly autonomous in every possible way? Does it and only it use its own data store or does it share it with other services?

- These are simple questions that when answered, can potentially highlight whether or not your newly decomposed monolith has indeed been decomposed in to microservices correctly or whether you are still within the distributed monolith phase.

- Event Storming is a popular workshop technique that helps both development and their related business teams correctly model their domains and reduces the possibility of a lack of understanding that results in overlapping domains that is reflected within the software product.

Image Source: http://www.karam.io/2019/Microservices-101-The-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly/

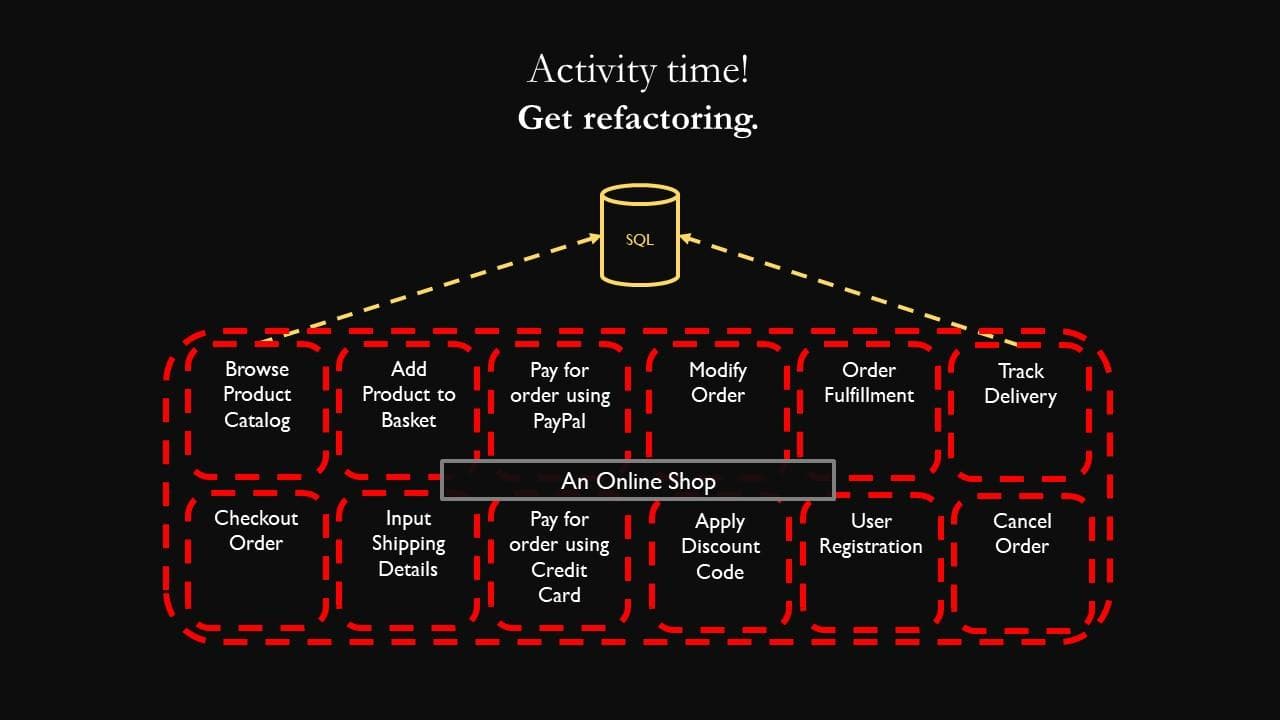

The Gateway Drug Workshop

- The main participatory part of the two day workshop at NDC London was an introductory session to Event Storming which I will cover in another future post.

- In the mean time, for my first session of relaying the contents of this post back to the IT department at work, I came up with a simple taster activity just to get the blood flowing a little bit in groups and give people a break from listening to me babble on poorly about the pros and cons discussed above.

- My aim was to get people stood up, communicating, collaborating and most importantly realising how difficult it genuinely, really can be to decompose and re-architect large software systems alongside highlighting the importance of why in order to truly reap the benefits, bounded contexts or domain boundaries must be defined correctly.

- The workshop was a simple diagram of an online shop monolithic application with clues as to what functionality the application currently holds and I asked teams to not only try and define how they would decide to split the application in to microservices but to also come up with 1 advantage they could gain from doing so.

- Most teams ended up with roughly the same sort of split of services. Splits that are clearly hinted at within the monolith diagram such as the mention of a Product Catalog, immediately triggering the need for some sort of Products aggregation and of course the most popular one which is some sort of Payment aggregation.

- However, nobody considered any sort of Warehouse or Fulfillment concerns. For example, when a customer cancels an order, surely we then need some sort of way to stop the delivery leaving the warehouse? This highlighted that whilst as developers, we can look at something such as this and think "why do I need to involve my non-techie stakeholders with the decomposition of my software system? I'm the expert, I'll just code what I think is right.", it isn't actually that simple.

- Another interesting one was how different teams dealt with the fact that the monolith could deal with the application of discount codes. Some teams here assumed that this would exist within the boundary of some sort of Basket or Checkout aggregation whilst others assumed that it would actually be separate and live in its own separate Promotions or Retail aggregation. This separation also existing highlights how complex and how sub-layered a business domain such as sales can really be which we do not always realise at first glance.

- It's a similar concept to when developers give estimates and don't realise how monumentally off their estimate they really are until they actually get stuck in to the task.

- So in conclusion, when it comes to decomposing monolithic applications and deciding where to draw your bounded contexts and what they should contain, it matters less how you - the technical person - think it should be decomposed and instead you should let the bounded contexts be drawn automatically by the correct modelling of your business domains which can be achieved by working with the business.

Domain-Driven Design

- Martin Fowler defines Domain-Driven Design as being about "designing software based on models of the underlying domain, using ubiquitous language to help communication between software developers and domain experts. It also acts as the conceptual foundation for the design of the software itself - how it's broken into objects or functions. To be effective, a model needs to be consistent so that there are no contradictions within it". I strongly recommend you read his article linked to above and focus on the examples given.

- From a microservices perspective, Domain-Driven Design aims to help us decouple and decompose systems through the identification of bounded contexts/service boundaries. It is through the identification of those bounded contexts that ensures our model contains no contradictions within it. This will then help us define truly autonomous microservices.

- Carrying on with the ecommerce business example where a customer could be both someone who we are selling to or someone who has already been sold to and is now being addressed via after care support. If we put it all together and look at it from a development point of view and how having defined our bounded contexts before hand helps us, if the bounded context described above isn't correctly defined, at first glance developers may feel the need to have some sort of customer service that might provide the ability for other services to do all sorts of customer related bits of functionality such as tie them to an order or support ticket. The issue here is that eventually down the line, it will become clear that this service is providing necessary functionality that both the Sales domain of the business and Customer Support domain of the business are tied to. For example, one development team have to make and deploy a change to do with adding extra fraud validation that is executed when a sale is about to be made. This has nothing to do with any aftercare support software function as this second development team because it is a sales only concern. Is there toe treading here? Who actually owns this so-called service? Can you now see where this is going?

- So by utilising a workshop technique such as Event Storming where the business starts by listing all the domain events, this could result in a high level event being listed along the lines of "Customer Account Retrieved", "Customer Assigned to Ticket", "Support Agent Assigned to Ticket" & "Customer Support Ticket Created". Bingo.

- Naturally as the workshop progresses, it will become clear that the "Customer Assigned to Ticket" event clearly belongs within some sort of Customer Support bounded context and thus drives where the software implementation of this event lives rather than live with other software to do with specific Customer Sales.

- It is much easier and cheaper for us to make changes to sticky notes stuck to a wall, than it is to make significant code changes later down the line. This is why event storming is fantastic as it allows us to identify these problems, before they come to fruition.

Ubiquitous Language

- Event storming sessions are also incredibly useful for developers to take note of the language used by the business when talking about different parts of their domains.

- By the end of the sessions, if events have been written in the past tense as the inventor of event storming - Alberto Brandolini - suggests, it is quite easy to translate them in to events within the code (think Event Sourcing).

- If in the long run, code is written in the language of the business, it should result in it remaining comprehensible for both parties.

Q&A

Here are some questions along with their answers, that were asked after the session.

Q: Who are amongst the biggest advocates of microservices?

A: ThoughtWorks, Netflix, Spotify & Google have provided plenty of content around the topic over the past couple of years.

Q: Is it on the contrary, not actually easier for new recruited developers to deal with one large application than try to understand and navigate around lots of smaller ones?

A: For inexperienced developers who are used to only ever working on one codebase at once, perhaps so. Otherwise probably not, because code is code regardless of where it lives and regardless whether it executes in one project or several smaller projects that interact together. To an extent, this is like suggesting we should put all our code in one file because it's easier to read when it is all in one place. The biggest difficulty for most developers who are new to a codebase is most likely not being able to read, understand, comprehend & make limited functional changes to the code but actually understanding the context and purpose behind why it was written in the first place and whom it was written to serve which holds them back from designing larger changes. Once the developer understands the business domain and hopefully comes to terms with the ubiquitous language used also within the code, everything will make sense regardless of whether it is one big single project or many smaller ones. You could argue that exposing the new recruit to work on one independent and focused smaller area of the domain at once is a better approach. As software developers, we should feel a sense of responsibility to fully understand the business domain for which we cater and write software for.

Q: Should I start developing my new systems/applications/greenfield projects as microservices?

A: No. Start with a monolith first and then decompose later if you genuinely think there is value in doing so.

Q: Are microservices always small?

A: No, the name is misleading. Model based on your bounded contexts. Codebase size is irrelevant as long as the service itself is truly autonomous.

Q: When do I know when I need to start decomposing an application in to microservices?

A: Are you currently experiencing problems with your monolith/distributed monolith?

- Yes? Continue.

- No? Don't bother, however consider your current implementation against the principles of DDD and determine whether your software could benefit from a simpler level of functional decomposition.

A: Do the benefits discussed above, solve all of the problems you are experiencing with your monolith and can you afford to deal with the trade-offs as well as have the required CI/CD in place?

- Yes? Continue.

- No? If you feel the benefits of microservices are for you, consider the cost of moving the blocker that is stopping you from getting there. Otherwise don't bother and instead consider your current implementation against the principles of DDD and determine whether your software could benefit from a simpler level of functional decomposition.

A: Do you intend on using DDD/Event Storming as a way of driving your transition from monolith to microservices?

- Yes? Awesome. Remember to take it slow and work on extracting one bounded context at a time. Look in to a technique called the Strangler pattern.

- No? Proceed with caution, make sure your alerting and monitoring is on point, good luck.

Q: I have some code functionality that is used by more than one area of my application and will need to be used by more than one of my potential microservices. Should that functionality therefore also become a microservice even though it may not map to a specific business function?

A: In Sam Newman's book called Building Microservices, he states "Don't violate DRY (Don't repeat yourself) within a microservice, but be relaxed about violating DRY across all services. The evils of too much coupling between services are far worse than the problems caused by code duplication". One option is to consider a package/library (assuming it does not contain business logic, otherwise go back to the drawing board but also bare in mind the trade-offs that approach comes with regarding what impact package updates/versioning could have across the applications that hold that dependency. Otherwise it is considered fine to create common microservices as long as we ensure we take in to account fault tolerance (e.g. using circuit breakers).

Q: Is each bounded context found in the event storming process, a microservice?

A: It depends. Event storming can be both a very high level process just for domain modelling or a very detailed process to derive exact bounded contexts. Assuming a bounded context is defined as some sort of logical boundary where everything within said boundary is its own responsibility. The high level workshop we did started by identifying domain events, followed by the actors and commands that instigate the events, followed by grouping different domain events in to aggregates with similar responsibilities that then come together to make up several bounded contexts. However, this also doesn't mean that each aggregate isn't also theoretically a bounded context within its own bounded context either. You may find that some identified bounded contexts are better decomposed in to more than one microservice which you might split based on the aggregates within.

Q: Why are microservices on hold on ThoughtWork's technology radar?

A: The Chief Technology Officer at ThoughtWorks, Rebecca Parsons, has answered this concern here.

Q: What about when we make everything so fine grained that we have 500 microservices to try and manage?

A: Say an average software development team contains 5 developers. If that software development team are domain aligned, I'd be very surprised if you ended up with a ratio of more than 1:5 services per developer which would roughly equate to 25 services. I'd recommend occasional pair programming rotations within the team to ensure knowledge silos do not occur if that is something you are paranoid about.

Q: I still don't think microservices is for me.

A: Well, it isn't, for a lot of people and projects. It is merely an architectural style that serves certain purposes and comes with several resultant trade-offs like many other software development architectural approaches out there. Ultimately as software developers, it's down to us to ensure that we are making the right, informed decisions by analysing trade-offs and then doing what we believe is right thing to do.

Q: Isn't Domain-Driven Design more of a business concern? Shouldn't the business be coming to us and trying to get us on board rather than vice versa?

A: It doesn't matter whether you're a software developer or someone from the business, at the end of the day if teams are domain aligned, both the development team for that domain and the business team for that domain should be actively working together to deliver their function for the wider business. If we feel we should be doing something different for the greater good, we should feel a sense of obligation to do whatever it takes to achieve it and in this case take on the responsibility ourselves to try and do whatever it takes to get to the better place we think we can reach.

&emoji=&slug=karam&button_colour=FFDD00&font_colour=000000&font_family=Comic&outline_colour=000000&coffee_colour=ffffff)